Copyright © 2023 Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center. All rights reserved.

- [email protected]

- 1960 National Ave, San Diego, CA. 92113

Aztec Brewing Company opened in Mexicali in 1921. The brewery was started by a pair of San Diego businessmen, Edward P. Baker and Herbert Jaffe, as well as the brewing engineer William H. Strouse. They chose Mexicali as the location because Prohibition was in effect in 1921, and therefore no alcohol was being manufactured or sold in the United States. The Brewery operated and flourished in Mexicali, with its trademark pale lager, A.B.C. Beer winning a gold medal at the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 in Seville, Spain. With the end of Prohibition in 1933, Aztec Brewing Company made plans to relocate to Logan Heights in San Diego.

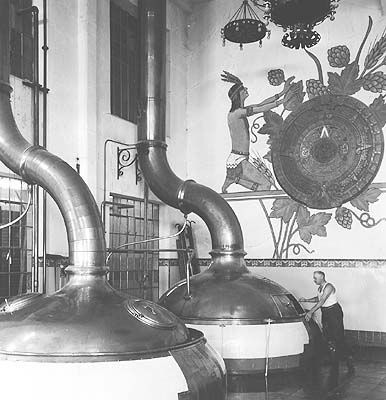

When the brewery opened in Logan Heights, a great deal of remodeling was necessary to convert the space from an old tire plant to a brewery. Beyond the obvious requirements of brewing and bottling materials, the company also aimed to create a unique and culturally relevant tasting room where visitors could enjoy the brewery’s product. This room would become known as the Rathskeller, and it is difficult to imagine that the owners of Aztec Brewing Company were aware at the time of the impact the decoration of the Rathskeller would have on Logan Heights and the Chicano community in the years to come.

When Aztec Brewing Company sought an artist to design the Rathskeller, they turned to a somewhat ironic source-a Spanish muralist by the name of Jose Moya del Pino. At this point in time, Moya del Pino had garnered international recognition and renown for his work, and had even developed a presence in California after he had been sent by King Alfonso XIII on a “cultural tour” of the United States. Moya del Pino’s tour was blindsided when Spain’s government failed, which caused his funding to cease[1]. As a result, he began painting murals for money, and his work included the Coit tower in San Francisco and Acme Brewing Company, as well as a few other Bay Area sites. Eventually, he was commissioned by Aztec Brewing Company to create murals and artwork for the Rathskeller.

Jose Moya del Pino drew artistic inspiration from Mexican muralists, citing Diego Rivera as a major influence. So, when he was selected to contribute the artwork for the Rathskeller, he aimed to create a traditional and culturally relevant theme of artwork for the tasting room. While Moya del Pino did not grow up in Mexico and was educated in Spain, he painted the murals in accordance with Aztec and Mayan traditions. The result was an astonishing collection of monumental-style murals that depicted the region’s landscapes, people, and culture. It is indeed slightly ironic that, of all people, a Spanish artist was summoned to Aztlán to create artwork celebrating the area’s rich cultural history. However, Moya del Pino was mindful of this, and his artwork was renowned for years to come.

Salvador Torres came across this image in 1988. [2] Shortly after seeing it, he decided to go to the former site of the Aztec Brewery and see the images for himself, describing his experience by saying, “it was like walking into a temple.”[3] Around this same time, it had been determined that the building was no longer functional or safe, and the only option was demolition. Upon seeing the intricate artwork in the Rathskeller, Torres immediately became poised to preserve it at all costs. He felt that he had discovered something of an artistic phenomenon, a missing piece to a connection between a Spanish artist and the Mayan and Aztec tradition in Aztlán. [4] Here it was, a contribution from a nation long associated with conquering this territory, and yet Torres, rather than seeing it as an adversarial relationship, saw it as a beautiful event. Torres could see that it was a celebration of the rich history of Aztlán, and so he welcomed the artwork of Jose Moya del Pino.

Salvador “Queso” Torres is known to many for his contributions to the establishment of Chicano Park in Logan Heights, which included fighting for the Park’s right to exist as well as his work on the murals themselves. As Chairman of the Chicano Park Arts Council, Inc. Torres took it upon himself to address the San Diego Historical Site Board in an effort to save the Aztec Brewing Company from its impending demise. He even authored a short poem entitled “Ode to International Aztlán Museum” in which he reveres the work of Moya del Pino and proclaims that he and the Chicano Community will stop at nothing to preserve the artwork, stating that the preservation of the artwork is instrumental in saving the role of the culture of Aztlán in San Diego.[5] While Jose Moya del Pino was not the only artist to work on the Rathskeller (American artist Eugene Taylor made his share of contributions, as well as others), he is the artist whom Torres felt most inclined to recognize[6]. Further, despite the fact that Jose Moya del Pino was not by definition Chicano, Torres was adamant that his work on the Rathskeller room was a tremendous contribution to Chicano art and culture. With this began Torres’s tireless battle to rescue the Aztec Brewing Company’s artwork from destruction and have it placed, along with the entire Rathskeller room, in the sculpture area within Chicano Park.

Salvador Torres understood something extremely important, which is that art is often the longest surviving aspect of a culture. It was likely this same thinking that drove Torres in his efforts to establish Chicano Park during the construction of the Coronado Bridge. He knew that if nothing tangible is preserved, then even the history can be removed, and the cultural identity of a community can be altered with little to no regard for its prior inhabitants. He writes in his poem, “Ode to International Aztlán Museum”:

For if this is how

San diego can forget

Our Hispanic masters

Of fine art

How then will we be remembered?[7]

Torres sought to prevent this from happening, despite the challenges facing the Chicano Community in Logan Heights. If a bridge was going to slice through the community, then the members of the community were going to be able to leave their mark on what used to be theirs. With this in mind, Torres began to work to preserve all of the Chicano artwork in the region for the sake of cultural preservation and recognition. He saw the artwork in the Rathskeller as an undeniably important piece of the Chicano tradition.

While he may not have gotten everything he wanted, Torres’s efforts did pay off. In the late 1980s, the artwork was saved by a collection of Logan Heights residents, and in 1990, with the demolition of the old Aztec Brewing Company location, the San Diego City Council declared the artwork as historic and claimed it, vowing to restore it and eventually place it back in Logan Heights.[8] Not all of the artwork was restored and returned to the community, however. For example, a large Aztec calendar (shown below), much to the dismay of Torres, did not make it back to the community after the demolition.

Still, a great deal of the artwork, including the murals painted by Moya del Pino, as well as stained-glass windows, paintings, wooden columns and beams from the Rathskeller, chandeliers, chairs, and an intricately designed bar were rescued from the brewery before its destruction. The artwork remained in storage for more than two decades until it was finally given back to the community, as promised. In 2014, the artwork was finally donated to the Logan Heights Library and placed on display all throughout the facility. One library employee described the introduction of the artwork in the Logan Heights Library as “a huge unveiling,” going on to say that the artwork, “is very important to the community because of it cultural significance.” The Logan Heights Library is situated near several middle and elementary schools and serves as a place for young members of the community to learn and grow. With the addition of the artwork, the youth is given exposure to even more historic and culturally relevant artwork in Logan Heights, which is something Salvador Torres sees as very important. In the end, Torres may not have gotten exactly what he was looking for. However, due to his persistence and resolve, along with the support of the community of artists in Logan, he was able to save a large collection of timeless pieces from what appeared to be inevitable doom. Instead, the artwork will now be passed down to the youth and future generations in Logan Heights, thus further establishing the Chicano Community’s identity in the region and ensuring the recognition of the history attributed to the heritage. With this, after many years of relentless work, it is clear that Salvador Torres and the community’s efforts to rescue the artwork from the historic Aztec Brewing Company were not made in vain.

By: Ryan Hand

[1] voiceofsandiego.org

[2] voiceofsandiego.org

[3] voiceofsandiego.org

[4] voiceofsandiego.org

[5] voiceofsandiego.org

[6] Laprensa-sandiego.org

[7] Salvador Torres. “Ode to International Aztlán Museum”

[8] Angela Carone. KPBS.org

Notes:

http://www.voiceofsandiego.org/beer-policy/a-brewerys-vivid-artwork-mothballed-for-years/

http://www.kpbs.org/news/2014/nov/11/mothballed-aztec-brewery-artwork-gets-new-life-lib/

http://laprensa-sandiego.org/featured/historic-aztec-brewing-company-art-is-back-in-barrio-logan/

Torres, Salvador. “Ode to International Aztlán Museum”. Publication info unknown.