Copyright © 2023 Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center. All rights reserved.

- [email protected]

- 1960 National Ave, San Diego, CA. 92113

Neighborhood House/Big Neighbor

1809 National Avenue

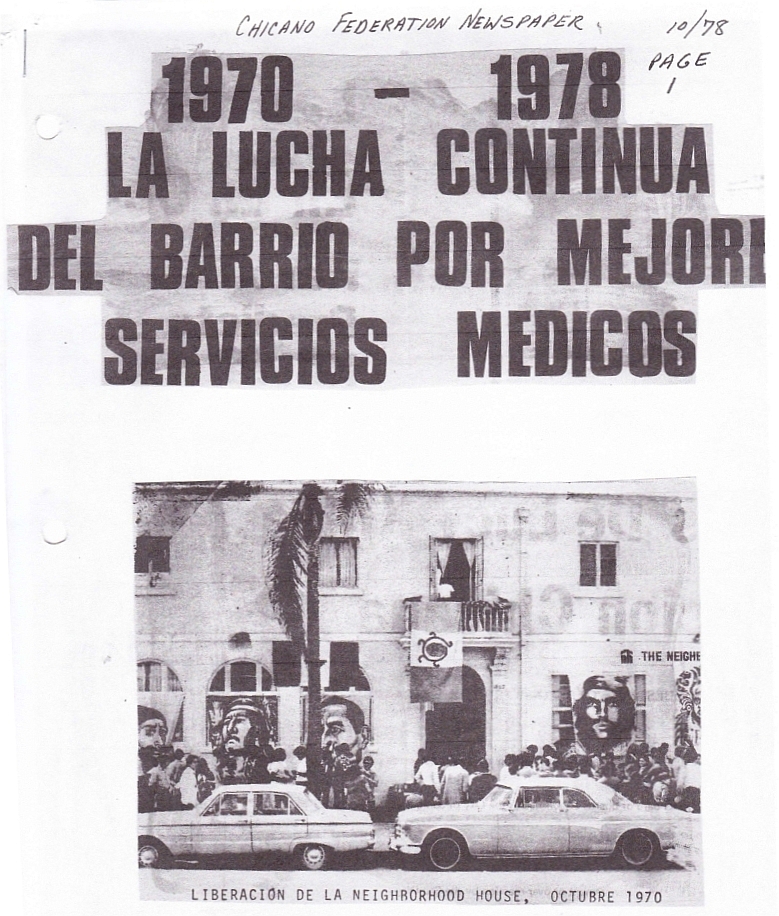

The takeover and occupation of Chicano Park in April 1970 provides an important backdrop to understand the occupation and takeover of the Neighborhood House in October of 1970. The original Neighborhood House – known as Big Neighbor to community members in Logan Heights – was occupied by Chicano activists who envisioned that community empowerment, rather than federal influence outside of the community, would determine social services to ensure vitality and health in the community. Through the occupation of Big Neighbor, the Chicano Clinic was created and vital social services that were locally-based and relevant to the community returned to Logan Heights.

It is important to understand the history of Big Neighbor, as the memories surrounding the occupation may not be widely recognized outside of those who were alive during this period of occupation. Additionally, Big Neighbor represents much more in the hearts and minds of generations of Logan Heights residents than dominant history-makers make it seem. The occupation of Big Neighbor was one moment in the larger Chicano movement where community members created and nurtured community-based leadership, activism, and the celebration of Chicano history and culture in Logan Heights.

It must be acknowledged that this summary would not be possible without the incredible work, devotion, and love of Maria E. Garcia. A retired school principal, Garcia has done activist work in the Chicano movement since 1968. Her series on the Neighborhood House provided the majority of information in this summary, and a link to the larger, more detailed, and community-based historic project can be found at the conclusion of the article.

From its inception in the 1920s, the Neighborhood House served as a settlement house, where poor working-class folks could access social services, cultural activities, and community-building opportunities. The Neighborhood House was unique as it served a primarily Mexican American population and was the closest settlement houses to the U.S-Mexico Border. At the same time, one of the goals of the settlement house movement was to Americanize and assimilate the immigrant populations they served. During the period between the Depression and World War II, the Neighborhood House did this by offering educational services, cooking classes for boys and girls, sewing classes, summer camps, sport leagues and teams, and an increasingly popular free health clinic, among other programs to the community. Although Anglo-American cultural values may have been predominant through these programs and services, Big Neighbor was the only public agency devoted to delivering health and social services to the Chicano/Latino residents of Logan Heights during this time.

Tensions that led to the occupation of Big Neighbor in October of 1970 were rooted in national and local socio-political changes the Logan Heights community experienced after World War II. The community identified the displacement of Logan residents due to increased military presence in the bay after World War II, the expansion of the shipbuilding industry, the forced construction of freeways and the Coronado Bridge that divided the community, and zoning changes that favored large junkyards and industrial companies rather than longtime residences as issues impacting the community. Additionally, the Johnson administration’s Great Society federal social welfare policies replaced progressive era policies that originally constituted the philosophy and work of Big Neighbor. These changes were felt by community members who utilized the services at Big Neighbor; for instance, outside organizations hosted their classes at the Neighborhood House more frequently, the War on Poverty replaced existing preschool programs enjoyed by the community with Headstart Classes that, while appreciated, did not respond to the unique needs of the community, and very few Mexican-Americans held positions on the board of directors. It was at this point the Neighborhood House became less of a community hub.

1969 and 1970 were decisive years that Chicanos/Latinos in San Diego engaged in Chicano movement activism and empowered themselves as a community. In April of 1969, the Plan de Santa Bárbara – a radical plan for higher education – encouraged and engaged college students to become more active in Chicano community concerns. While Chicanos pursued higher education and demanded culturally relevant curriculum, they also maintained consciousness about what was happening at the local level in Logan Heights.

The occupation and creation of Chicano Park was born in April of 1970; this history is detailed in another section of the Logan Heights Archival Project, as well as through the link to Maria E. Garcia’s history of the Neighborhood House at the end of this summary. Big Neighbor played an important role in the creation of Chicano Park; for instance, the first meeting about the takeover of the park happened within the space of the Neighborhood House. The community empowerment experienced by activists engaged with Chicano Park provided the energy and momentum that inspired the occupation of Big Neighbor. This energy – amidst the accomplishments of the Farmworkers Movement and the overall Chicano movement throughout California and the United States – aided the Logan Heights community in feeling united to occupy and takeover Big Neighbor.

The occupation of Big Neighbor began on October 4, 1970, which was six months after the takeover of Chicano Park. Barrio activist Laura Rodriguez and Jose Gomez encouraged Maria Garcia to attend a meeting of the Community Action Council, where the occupation of Big Neighbor would be announced. The Community Action Council met at Lowell School, which was a block from Big Neighbor; a short meeting about the community’s concerns ensued, and once over, people walked to Big Neighbor to see if anything was happening. Laura Rodriguez chained herself to the Neighborhood House doors, cop cars circled the neighborhood, residents joined one another, and an energetic excitement took over the neighborhood’s atmosphere. On October 5, 1970, residents, Brown Berets, and MEChA students occupied Big Neighbor. These folks and many others involved with the Chicano Park takeover demanded that the community have primary control over the decisions that affected the lives of Logan Heights residents and the services at Big Neighbor.

The Chicano Federation identified six demands that they wanted to see immediately implemented at Big Neighbor. These demands included the immediate release of Ruby Hubert, Mr. Huseo, Anna Brown, Eddie Oriole from their positions in the Neighborhood House, the implementation of social services – such as child care, English classes for Spanish-speaking folks, food distribution programs – and the election of a new board of directors made up strictly of local residents. In terms of the new health services that Chicano activists demanded, they envisioned Big Neighbor as having a free dental clinic, a day care center, recreational events, a library started by Maria E. Garcia, and the return of the beloved Coach Pinkerton to assist in the implementation of the recreational programs. Evidently, activists valued community determination in the creation of local programs at Big Neighbor.

Coverage of the beginning stages of the occupation did not begin until October 7, 1970 with Jose Gomez – an instrumental activist in the Chicano Park takeover – as the spokesperson for the occupation of Big Neighbor. The activists valued community determination in the creation of local programs at Big Neighbor, which was evident through the proposed programs for the Chicano Clinic. Those that were on the negotiating committee with the old board of directors and the Chicano activists were Leonard Fierro, David Rico, Tommie Camarillo, Laura Rodriquez, Angie Avila and Maria E. Garcia. For weeks, these folks released payroll records, distributed food meant for poor families – but that was potentially given to friends and family of the board of directors – to the intended recipients and started a free breakfast program for children that came before a federal free breakfast program.

On December 6, 1970, San Diego police entered Big Neighbor and arrested all those who occupied the space. Prominent activists – Rico Bueno, Jose Gomez, David Rico, Manuel Sabin and Kiki Ortega – were arrested and eventually released a week later due to community protests for their release. When the occupation ended, the official representation of Big Neighbor moved out of the National Avenue location. The Chicano Free Clinic was established and provided health services in line with the activist visions articulated at the beginning of the occupation. The Logan Heights community and Chicano activists hosted fundraising events and community activities to maintain the services provided by the Clinic. Three years later, the Chicano Free Clinic was incorporated into the Family Health Centers of San Diego, which was also found and funded by Laura Rodriguez.

The occupation strategies that solidified the takeover of Big Neighbor represent an important moment in Chicano activism within San Diego. The occupation happened after the takeover of Chicano Park, but also happened before the takeover and creation of the Centro Cultural de la Raza in Balboa Park. This history is vitally important to document and maintain, and oftentimes remains overlooked by local, state, and national officials. Not only does Big Neighbor provide a rich history of resistance and survival, but the stories that encompass Big Neighbor can serve as inspiration for current activist campaigns within Logan Heights.

~~

For specific stories, interviews, community memories, and more detailed accounts of Big Neighbor, visit Maria Garcia’s History of Neighborhood House in Logan Heights series on the San Diego Free Press: http://sandiegofreepress.org/category/columns/history-of-neighborhood-house/